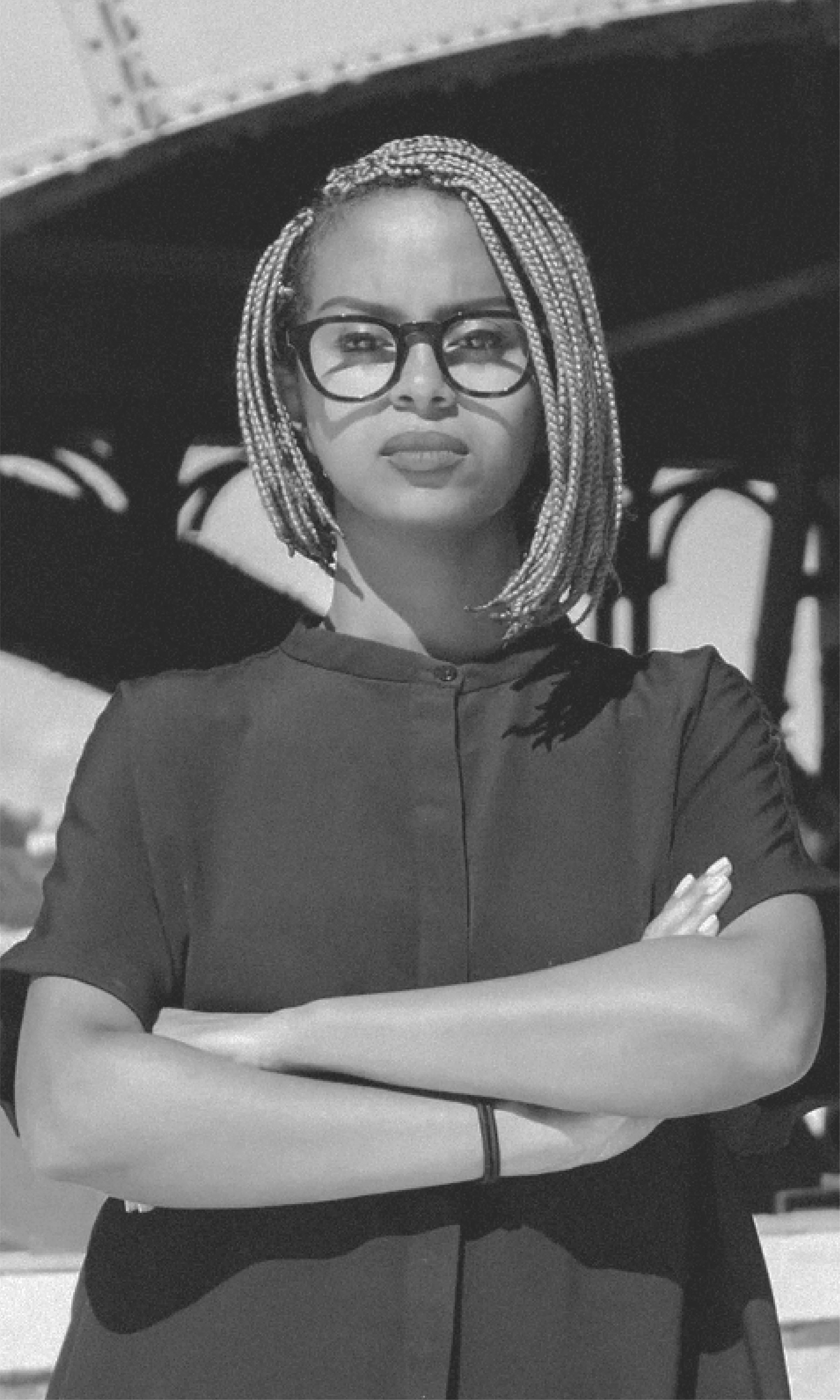

Sara Zewde on Landscape Psychology and The Craft of Construction

Show contributors: Neil Ramsey, Marquise Stillwell and Sara Zewde

Audio engineering by Hasan Insane

Sara Zewde photographed by Gladimir Gelin.

In this week’s conversation, I speak with Sara Zewde, principal of Studio Zewde, the Harlem-based landscape architecture, urban design, and public art firm. Sara is Assistant Professor of Practice at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and is the recipient of a number of awards, including the Hebbert Award for Contribution to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT and the Silberburg Memorial Award for Urban Design.

Sara was named the 2014 National Olmsted Scholar by the Landscape Architecture Foundation, a 2016 Artist-in-Residence at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, and in 2018, was named to the National Trust for Historic Preservation's inaugural “40 Under 40” list. Most recently, she was named a 2020 United States Artists Fellow. We explore her voluminous and wide-ranging design methodology - a practice that’s powered by site interpretation, cultural narrative, and a dedication to the craft of construction. Zewde’s philosophy centers on shaping the spaces she designs to reflect and respect their psychological impact on those who will inhabit them.

Listen on Simplecast | Spotify | Apple/iTunes | Podtail

TRANSCRIPT

Marquise Stillwell

Welcome to the Sweet Flypaper podcast. My name is Marquise Stillwell.

Neil Ramsay

And I am Neil Ramsay.

MS

And today we have Sara Zewde. She is a landscape architect, but that's just what you would look at when you think about her work. She has such a wide ranging design methodology, and the way that she interprets and brings cultural narratives into her work is beautiful. And so I had the pleasure of sitting down and then speaking with her.

NR

You said these cultural narratives into the work. And she's a landscape architect, and this is not a statement, and maybe you have something to say about this, but the cultural narrative. It sounds like a modern term, like something we hear now. But it's one of those, well, why haven't we been saying this and why aren't we using this and how comes this is not integrated into all that we're doing? Like, I'm in a university institution. I mean, this has to be about cultural narratives, you know?

MS

Absolutely. Part of what we talked about, Sara and I, were just thinking about how as a landscape architect, really what you're doing is scraping away evidence, right? And so the cultural narrative is that you're revealing truth or you're revealing also what has been hidden. And the work that she does is really to reveal that truth, whether it is the truth of who was at this land, what's beneath the surface? Sometimes literally and sometimes figuratively.

NR

Yes, both. I think, as I mentioned before and not sure if we I did mentioned before, but I'll just say it. Is that I was on this, I told you, part of a guest professor on the Rosewood Florida super studio overnight, looking at a cultural center and a museum and looking at a 23 acre site that was part of the Red Summer Massacre. And so what you just mentioned is very poignant, right? You know, just in that particular project, it really revealed to me, and this was led by landscape architecture and interior architecture and was part of the Green New Deal, but it really revealed to me on a lot of our conversation was the evidence that was lost of a flourishing community. You know, in the 20s before the massacre really was getting its foothold after emancipation, and then looking at also not replacing it, but removing the veneer. Right? It was more like removing a veneer that was put on the place so it can uncover the truth and the respectability and the evidence that occurred before. And let's look at that until up into this light.

MS

Well, it's kind of what you challenge before and our conversations around, should we start with the land and then go to the built environment? And I think that people are afraid to start with the land first. And I think that it exposes, is very vulnerable, to start thinking about how you shape the actual land in the area for which the building is going to sit. Which, I think to your point, that it's the way that we shouldn't do it.

NR

Yeah, I call it an ego check. And I think that's one of the reasons that not really cause or result, but I call it an ego check. When you have the honor of land and nature first.

MS

Yes, exactly.

NR

And then you engage, right? That's working with it as opposed to using it.

MS

Absolutely.

NR

And think about the language we often say we're going to use the land. It should be — what can we do with the land?

MS

Yes, right. And honor the land.

NR

You know, I think language is important. And I don't know if you've heard me say that, but I think sometimes the words that we use in speaking of these disciplines and how we approach things, there's a lot of energy in those words that takes on a gift. And I'm really an advocate for gifting with our words and really thinking about what we're seeing in terms of that. So it's like, how do we work with the land. Just that, as opposed to using it?

MS

Absolutely. Well, let's listen to Sara.

MS

So, Sara, welcome. Thank you so much for agreeing to be a guest with me and have this conversation. What I like to do is instead of just going through, the bio based on what's been written, I'd love for you to describe what do you do? How do you describe what you do?

Sara Zewde

Hmm. Yeah. Landscape architect doesn't really resonate with most people. But I make places. I would even hesitate to even say that because it suggests that places don't exist, but I shape them, right? As a profession. It's weird to talk about yourself as having like kind of a God-like role in the earth. So even to say that that's my profession is like challenging. It’s hard to even say those words, because there’s so many processes, natural social, political, ecological that I'm navigating and all the time. And I'm a small role in that, but I do take part in the shaping of landscapes. It took me awhile to arrive there, but I think those are the right words.

MS

Yeah, no, I mean, that fits really well. And, language is so important, which is why I ask. And as you live, going through this process, particularly the education process, there was so much language that you had to edit to even start to think about seeing yourself, and seeing the work that you would like to reveal to the world. Talk a little bit about that process and through education and getting to where you are today. How did you navigate the process of editing to get to a place where you're actually starting to tell stories?

SZ

You started with big questions. Well, I grew up in Slidell, Louisiana. I'm a product of public schools in the state ranked 50th. So it probably starts there: trying to understand myself and this culture and this place that I grew up in and the culture of my own family and just that never resonating with things that were happening with, in school, in the classroom. And that consciousness was always with me from childhood. And that extends all the way to August of 2005, when hurricane Katrina hit. And I watched that from my dorm room in Boston, my college dorm room. And, thinking about the education I was there to pursue and the connection between what was happening in Louisiana and what I was learning.

And so that was also kind of another turning point where I had some intentionality about trying to pick a profession and trying to find a framework that might be a place that I could start to give union to the things that mattered to me and how I understand the world and a skillset. So long story short, I guess I did multiple degrees and, tried different realms of thinking and found ultimately landscape architecture to be this set of skills that I could apply, even though I wasn't being taught to do so. I found it to represent a toolbox that I could apply to really engage with the things that I was interested in in the world.

MS

I can see that and I bring that up because when I look at your work, not only do I see how you're creating these new conditions and working with not only just the landscape, but the story that goes beyond maybe the particular site. Brazil is a good example of that. I can see how you're editing along the way, and almost like editing through uncovering deeper stories and wanted to really get a sense of your process and how you think about projects that you want to get into.

SZ

It's so interesting the word that you're using: editing, because there's always this like cognitive dissonance, Dubois calls it a double consciousness, between the, the environment, the physical environment, especially the built environment, which is an expression of power and capital, and then, the human body. And so a lot of times we grow comfortable with that dissonance and we make do. And we try to form that union in ritual, in arts, in music, in culture, in Hip Hop, in the way we use space.

So I've always been curious about what places would look like when you are able to edit when you were able to bring those more in union. I remember. So when apartheid ended in ‘94, my dad was, this was the first time I left the country. My dad was like, well, let's pack up in the, see what South Africa looks like.

So we went and I remember being there and being like, why does it look like, I don't know. I haven't, it's like 10 years old. And I just was so confused about why it looked the way it did. I imagined Africa as I'm sure most people do or did, that Africa would be this place that looked very different because the people are very different and it didn't.

And so that registered a lot to me. And so I was just like, well, what would our worlds look like? And so that's always been, my place of exploration is trying to, bring that in union, trying to like express how we see and feel the world. What if our environment was designed to promote our identities, our cultures, our ways of life? That world probably looks very different. I feel like there's a lot of talk more now about this. I don't know. Even things like coming to America, Black Panther—and, I don't know, I see a lot of different realms of art and design and music exploring this idea. And that's why I'm, I'm actually very interested to have this conversation with you and hear your thoughts on it. Graphic designers are talking about this, content producers. I mean, there's just a lot of implications and so my little corner of that world is in landscape.

MS

Our friend Walter Hood would always argue that not landscape architecture, I'm an architect I help. I do as just as much as the built environment as we do.

And what you may think as the land environment, right? The spatial environment. And one thing that I do love about your work and just your lived experience, is that being a woman. Being a Black woman. We're constantly editing in our life. Right. As soon as we walk out the door and there we are, we get on the subway.

Are we going to tax her? We walk down the street, we're constantly navigating life, right? We're negotiating each moment that is coming at us and we are going at it. And so I say that because the world needs designers to be leaders. Right. They need us to take that lead. And I think that I can see, I see a lot of that in the expression of your work.

And I do see the both sides of where you're moving forward and then where you're editing along the way. And you're helping to create some of those edges. Right. Talk a little about the Brazil, the project in Rio. I think that that one really expresses on that and I, I love. Yeah, I knew a little bit of a story of how you got into it.

I just, I love the serendipity of, of how you came into that project, but for our listeners, give, give a little bit of how you get into that project and where you are with it today.

SZ

Serendipity is definitely the word. So, I mean, in a sense, the story starts in the 17th century.

MS

Let's go way back.

SZ

I mean, it actually starts 300 million years ago and here's why.

300 million years ago, the East coast of Brazil and the Southwest coast of Africa for one landmass and fast forward to about 500 years ago. What happened was a port was established along the coast of Brazil. The one that touched Africa and it became. The infamous point of disembarkation among trafficked Africans to the Americas.

And so 22% of all of the Africans enslaved and brought to the Americas landed in Rio De Janeiro now. And so for millions of them, the Willinga War is the point at which their feet first touched the soil and the Americas soil that 300 million years ago was in fact part of Africa. So after the abolishment of slavery, there were a number of landfilling operations and the stone jetty that represents that critical point in this history.

Was covered over and fast forward then to 2010, when the Olympics in the world cup happened and they found perfectly preserved below the street, the stone jetty. Wow. I happen to be working as a transportation planner in Brazil. That's a whole nother story. But again, part of my sort of professional exploration of, what do I, what do I want to do?

And this discovery was made. And so I just read about it in the newspaper. But I was starting to think about landscape architecture at the time. And so no one came back to America to go back to school, to study landscape architecture. And I was following the news about this discovery in the newspapers.

They were talking about how the Black community and Rio and activists were saying, you made this discovery, this really important material, evidence of the transatlantic slave trade, and you're just gonna. Keep going with your street construction projects. You have to do something. And so with some pressure, the mayor.

Said, we're going to design something that represents the Black experience in Brazil. And I just was like, I started studying landscape architecture at the time and I was like, what does that even mean? What does he know that I know about the discourse on Black design? So I got a research grant and I went down and basically, tried to ask the mayor or I did ask the mayor's office.

What is it? What did you mean when you said. That you were going to design something that represents the Black experience and the response was, we don't know, we just kind of said that, but if you have any ideas you can design it. I was like, okay. Wow. So I mean, I had fun and a number of relationships with community members at the time who were really fighting for this.

And so they were very supportive of my involvement. And so. 11 years later, I'm still working on it.

MS

Wow. Yep. It takes time. That's an amazing story. And congratulations on being able to land that project. And you went way back without research. I mean, you went way back. We give me a sense of your research process because as designers, researchers is core to the work that we do.

But I've, I've never gone back, millions of years. What made you decide to do that? What, what was a trigger or what was a moment that said, I need to go further back.

SZ

Was looking into effort, Brazilian culture as an entry point into designing the site. And I started to learn more about the botany of AFA Brazil and how a lot of the geniuses of the plants that they used were the same as Africans. And so that started to propel me towards like, wait, why are the plants the same between these two continents? And I've found that, because of this history, this geomorphological history of 300 million years, the soil profile of the continents are various of those particular points of Rio and essentially Angola are very similar. And so a lot of the people that were enslaved brought. Plants in the pharmacy with them and those plants flourished and hybridized and flourished, and then in the Americas. And so, I just kinda like pull it threads. Got it. It's not like a ha some people ask me sometimes like, well, what is your method research and what, what stepping and BNC I'm like, you just kind of, I kind of just follow the threads. I never know where it's gonna land. And there's just kind of a voice. And I think this is probably not helpful, but there's some level of just going towards where you, where things start to harmonize and, and moving towards that.

MS

Yeah. I mean, if there's a theme also in the way that you tell stories to not necessarily just memorialize, but to pull the memory of the stories forward is just the way that I, again, see it talk a little bit about that and how you do that.

SZ

That's an integrated question because to me, memorials and memory are two very different things, right. A Memorial, like a lot of what we know in the built environment is an architectural typology. That's worded in a very specific cultural history that primarily being Western Europe and it's rooted in notions of, of modern mentality and expressions, how power in dominance over the human body. And it's meant to, really it's fashioned around the idea of recalling a moment in time, a human, hero, a tragedy, or a triumph, war a battle, but in the context of transatlantic, slave trade, And a lot of Black memory in the diaspora, we're often not grappling with moments of time or outlier events.

We're talking about hundreds of years in this case. Millions of years. Yes. Yes. So that's adjusts that we design, we meet me, expand the design typology of the Memorial beyond an object on a pedestal or a wall with names. In the context of Black memory, it's really, it's a lived experience. And so, it's about designing in, in dialogue with life itself.

MS

Yeah. I mean, this is, go back to this idea of editing where you able, from what I've seen really distilled down this thing that, Hey, I'm not going to create this Memorial. But there is memory there and, and memory is filled with history and, and it's even in the food, we eat the DNA that dirt, everything, and even the story of those who made it, but we're dead on arrival and we're buried.

Became a part of the memory as we, she actually partake in the fruits, everything that right. And so there's a cycle, the other piece of, to what I've seen your work is this idea of building evidence of our existence. Right. And I know that some people may ask. I know I've seen it as the view and even with my work of, it's this Black design and visit just focus on that.

Like, how do you respond to that and the work that you do? Cause I know it's a question that. Comes up before us,

SZ

Every time I think about it and I have a different answer. So yeah. I feel different about it every time, because I can see it from all sides. Part of me is like, yeah, we have a cultural trajectory of aesthetics and know, that's continuous over a long period of time and we can innovate on that and make it contemporary. And other times I'm like, do we have to buy, is it automatically if Mark designed something you said, because I'm automatically Black. Cause there's that argument too. So I go back and forth and it's kind of how I feel that day. And I'm curious what your thoughts on it are, where you in on that argument.

MS

I agree. And I spent some time in South Africa, we did this film called shield and spear, and we worked with this group called the Black jacks. There was this Black funk band. And when the lead Sanger said, everything that we do unfortunately, is political.

He goes, even if I drew a Rose, it would be political here in South Africa. Right. And I think that in some ways, I own part of my narrative and it's my own, but I know that as soon as I walk out of my door, anything I do, whatever people want to see is what they were going to see. And if they need to see me as Black and the design I do as Black then.

Okay. But at the end of the day, I know that I'm, I'm a person, right? I'm a designer. This is what I love to do. And yet my lived experience helps to inform. The work I do. And so if that is the memory port forward of me and my ancestors, and that's the way that you see it, maybe because you don't know who you are then.

Okay. Maybe you're working through your thing, but for, at the end of the day, I'm a designer. I try to hold on to that narrative with everything that I do. And I can't necessarily separate my lived experience because I don't want to know again. It's it's we, we can't. So the big piece for me also is this the idea of evidence I'd love to hear you talk a little about the work you're doing.

You're helping to not only the pool memory forward. But to also like really create evidence. And I would say the work that you've done in Philadelphia on the two projects really helps to build that. But talk a little bit about those projects and how you worked closely with the community and, and how you helped to.

Established their evidence of their existence and everyone wants to erase us, but I think you're doing an amazing job of making sure we ain't going nowhere. Talk a little bit about those projects and how you work with community.

SZ

Yeah. I'm assuming you're talking about Mander and Brookfield up here. So, Mander is a 22 acre site adjacent to strawberry mansion.

And the park, this 22 acre portion of Fairmont park is the community's front yard. I mean, everyone, everyone we spoke to is like, Oh yeah, my first kids, I used to walk around here and I do this, and this is, this coach has football coach, gave me the determination I needed to get out of this neighborhood.

All this stuff happens. And then you go to this park and. There's no evidence of that, right? No evidence in the physical in, but if I show you pictures of this place, the way it is, there's that dissonance again, between how special, how remarkable this place is to people's everyday life and the investment that's actually needed.

It's about conditioning. Yeah. Yeah. The project became about, they want more than the community members gave us this poem. It says. Yeah, it asks the question. Can a monument that breeds feed up. Yeah, that's beautiful. And that became the creative departure for our design, the park. But in terms of process, every project I work on starts with a really rough patch at the beginning of mistrust.

And it's painful knowing that what kind of intention I'm bringing to the projects and. And being able to relate to that frustration. It's a very harrowing.

MS

Conditions that like the built environment means that they get to go inside or they have to go inside. Right. The idea of Black bodies, Brown bodies gathering outside people don't realize that right there.

There's the policing of that activity. Talk a little bit about that in relation to those projects, because. As a, architect to your landscape, you are probably building the most controversial space in cities.

SZ

Yeah. It's a really great point and something we wrestled with a lot. There's a project in Seattle where we were asked to do the temporary closet at a corner where more. Black men have been incarcerated at than any other spot in the city. And now you want us to make a bottle of it. Right. And, and a lot of that was for charges that had to do with marijuana. And since marijuana is now legal across the street from the corner is now a dispensary that's white owned.

MS

Wow.

SZ

So, we had a number of what we call design ciphers with people in the neighborhood to talk about this corner. It was actually a community group that wanted to do this, this closet, but it was very fraught for a lot of people. And two people started arguing at one of the ciphers, like, what is this corner supposed to be? And then the third person said it's supposed to be a place where you can have that argument.

So we started talking about the living room, designing the corner, like a living room and combating the idea that people aren't supposed to be there. That partner being so pleased, like, what is this space that makes you feel the most comfortable and at home? And so we designed the corner to be a living room and work with formerly incarcerated men from the neighborhood to actually design and install the concrete and, and everything.

And so it's a small kind of. Moment in the context of all of the systems that are at play, but, with reference to the point that you bring it's, it is very fraught to design a place that's supportive and anchoring of Black people in space.

MS

Yeah. I mean, you're, you're designing to reveal us right. Built environments. And I'm just playing off of this idea of reveal is to, to hide or allow people to go inside. Right. It's to protect it's to go inside is to disappear and you designed to reveal. It's allowing people to gather, and you're not only building the evidence of our existence, but you're creating the platform to allow people.

SZ

What's interesting that you say that because graffiti peers is about keeping us hidden.

MS

Talk about that. How does that play on the other side of, to keep us hidden?

SZ

Feeney is a sensitive ecosystem that thrives on being hidden.

MS

Yeah. And I know some of the graffiti artists in Philly, I mean, it is a underground. Yeah. But tell me a little bit about the research you did and what, what did you discover through that process?

SZ

Well, you know, because there's the graffiti writers are criminalized for behavior, their use of this particular site, and they have day jobs and, government names and monikers. It's all about the hidden.

And so actually our communication usually is very public, but what we proposed in this instance was to. Tap into the network and gain trust kind of off the record. And we found ourselves meeting people in random environments and getting representatives sent to us and communicating over physical mail and getting anonymous notes.

MS

Did you have a graffiti name? What was your graffiti? And did you change your name? Okay.

SZ

I was a radio show DJ and I did have, so I did everything during name.

MS

What's your DJ name, come on. No, one's gotten this information. Yeah I'm going Oprah on you. Does Harvard know about the DJ?

SZ

Like embarrassing. But so that was how that worked and we really tapped into the network. And what was most critical to them was. Maintaining that anonymity. So that could be, could continue to thrive in this place. So, it's really actually being more, more than revealing places of people across the board.

It's more about amplifying the culture that is there now in whatever form it takes, it's about amplification. And so it's like tapping into the frequency and just being like, all right, that's what you want. You better get it.

MS

Right. Right, right. So you've done all these amazing projects and now won some awards. And now you're teaching now you're going back in and almost like you have to re-edit you don't everything. And now you have the opportunity to push it forward of the books, the students, a syllabus, the narrative. Talk a little bit about that experience. Cause that has to be just a wild experience for you.

SZ

Mark is that to say you have very good questions. Like I've never spoken before. And I feel like I'm like, Oh yeah. I mean, because of that experience that I shared with you about my education and never feeling like that it was odd to turn the corner and really to understand actually what kind of freedom is given to professors, to faculty in the, in the Academy.

To your point, I'm like, wait, I can put anything on my syllabus? Nobody's gonna check—nobody—wait—I could talk about whatever I want? And then for that to be at an institution like Harvard is also daunting and you know, this is the first department of landscape architecture in the country. And so I very much don't take for granted that I have an opportunity to shape the discourse. And I'm trying to do that. I'm trying to bend it in our direction.

MS

Yeah. And I mean, your face is not represented well. You know, Black woman, who's walking through these halls and soon as you walk in, there you are. And I'm sure your students as well, when they come in, what are some of the, the books and some of the topics that you're exploring? And what does that start to look like for you as you're helping to shape the narrative?

SZ

Yeah, I mean, I, I found it recently that in the, these 125 year history of the department of landscape architecture at Harvard, I'm the first Black tenure track faculty.

Yeah. And a lot of how they teach the history of landscape is from this slave owning people. That's what the conceptualization and the history is rooted in. So the founder of our profession is a man named Frederick Law Olmsted. And I taught a class last semester about him.

He has a very interesting story. He like many of us didn't know what he wanted to do when he was growing up. And he, when he was 30 years old was hired by the New York times to travel the slave States and write about the conditions of slavery. And he became the most cited witness of 19th century slavery in America.

But the history of landscape architecture doesn't tell that part of the story. They just say, “Oh, this man invented landscape architecture. And then he made Central Park and then he made all the other parks in America.” So, when I found out that he had this history, I really wanted to dig into it. And so I'm writing a book about it now.

I retraced his steps through the self to track what he wrote, what he saw there 165 years ago. And what's there now.

MS

Did you go a million years back and see his great-great-grandparents or no?

SZ

I did. You’d have to read about it in the book. There is that. He's from Hartford, Connecticut. Yeah. Yes, I did. I did. I did it.

He thought he was going to the South to witness slavery and in reality, it followed around him for a long time. That's kind of, yeah, the short version of that. But yeah, it's like even their own history, even their own notable people, yhey don't tell the story of those people, right? And so I think that's interesting to kind of like— it's a Trojan horse in the sense, like nobody finds him problematic or challenging, but then you lift the hood a little bit and he's like, yeah.

And he's like, no, y'all are fucked up. Am I allowed to curse? I don't know. He's just like, owning humans is corrosive. You guys are drunk on this idea, and if we have any chance at a post-abolition, postbellum society, we need public land. We need landscape spaces because there is no civic culture. When you own humans, we don't, we can't form a society. He was like, there's obviously a moral argument against humans, but put that aside. There's not even an economic argument or a cultural or a societal one. And so in his mind, designing landscapes was a way forward for our society.

MS

Wow. Wow. And so you continue to come full circle, you have your practice and your teaching. What does the next couple of years, as we're transitioning into this new-ish world? For many of us for some of us, it's kind of like, okay, we've kind of seen this before. What does the next couple of years look like for you and how do you want to play, collaborate and build?

SZ

What kinds of things—what's going on for me, what, I mean, I definitely feel like for our office, it's an inflection point where it takes years to build the landscape. And so our first build projects are finishing construction and I really hope that continues. But while I dig deeper into those landscapes, I also want to be in dialogue with people like yourself who are in sister industries. And continue to check in about a couple of things. One is how do we make what we do as designers evident, clear, and open to people that are non- designers, everybody hangs out in the park at, live in Harlem.

Everybody hangs out with Marcus Garvey park. Everybody hangs out on the street. We can all talk about sneaker design. We can all talk about, you know what I'm saying? We can talk about a lot at me. We are really good at talking critiquing. I mean, I listen to a lot of like podcasts and stuff, and it's like, everybody's always taught critiquing things about like, how does a field like landscape architecture get engaged by the people who use them. So I think having cross-disciplinary conversations is something I really want to do in the next couple of years.

MS

Yeah. Well, we'd love to have you on Deem. So the reason why I connected you, like, we're thinking about design as a social practice and having an agent Marie Brown on the front cover for our first issue was.

Very much in line with the work that you do in way that she thinks about the environment and ecological concerns and how that is applied to who we are as human beings as well, and how we might live our lives in the way that B lives. And so I see there's this deeper correlation because you're also a writer.

As well. And I think that us sharing this, I want to appreciate you coming on. And I think, us beginning a dialogue and expanding this out is really important for design itself. Not just Black, like across the world. Our lived experience is really important to help you to change and edit the narrative.

So for the, thank you, thank you so much for coming on. Thank you for answering tough questions. Yeah.

SZ

Thank you for having me and, and, similarly in a spirit of exchange and calm response, it'd be great to have your, your voice and your experience. In conversations about landscapes. And, I think that's where innovation happens is when we're just cross- pollinating. And so, I can't wait to hear all of the episodes of this podcast and see what kinds of things start to emerge in that regard.

MS

Nope. That's it. Carrie was my first, like what was my second one relative to us. Yeah. Yeah. So I know that you guys are friends as well. Yeah. He's, he's amazing. And I wished, I mean, I was on the board of the Lowline. I don't know if you know that, but I wish I've known you during that time. The pull you down. Cause we work with Sydney. So she's a good friend of mind, but love to continue talking and seeing the work that you're doing. And I touch a lot of environmental and coastal work. And it's great to know that you are out there. You're doing the work — like doing the work, not just talking about the work and I really, really, really appreciate that. So thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

SZ

Thank you.